top-to-bottom, resilience is the new normal, and now is the new forever

Resilience (n):

The process and outcome of successfully adapting to difficult or challenging life experiences, especially through flexibility and adjustment to external and internal demands.

Architecture is an opportunity, a chance to improve on the processes and performance of predecessors across a broad spectrum of potential measuring sticks. In single-family residential, comfort, functionality, and on-trend style are likely to top homebuyers’ must-haves. Repeatable processes and readily available materials are fundamental to the builder’s profitability. Speed to market, saleability, and presence of place is what the developer is after. As for the architects and engineers, they seem to mainly want whatever they design to stand the test of time.

There is, however, a new now, which means a new normal. The catchphrase for the 21st Century – the new normal – is a ubiquitous explanation for what has become the reoccurring instant when suddenly the world turns upside down. We’ve had a few. High winds, flooding, fires, earthquakes, and plagues are age-old hazards, to which we’ve added man-made utility failures, chemical and radiological accidents, and terrorism. The latest, and greatest in terms of an overall impact on human health and wellness and the built environment must be the extreme weather events ravaging the globe and leaving a wake of devastation in their path.

And so today, the chance to change is not presented in the form of bells and whistles, or those that have and those that don’t. Rather, it’s a collection of easily implemented hows and whys that should be built into every new home from here forward. There are many resiliency measures for residential and even commercial structures that add tremendous long-term value and peace of mind for generations to come at little to no additional cost. Not so much a trend or buzzword, in architecture the new normal is resiliency, and the new forever starts right now.

“To build a resilient home or building you have to get the physics right,” says Rebecca Bryant, Principal at Watershed, a climate-centric design firm operating from Fairhope, AL. “Before you get into high-end systems or technologies, fundamentally the building form must be built to withstand extreme weather conditions. Where I live and practice along the Gulf Coast of Alabama, that means wind, water, and heat. For me, resiliency starts with a highly efficient, rock-solid building envelope that is attuned to the specific site and climatic circumstances.”

Bryant founded her firm during the 2008 recession, believing that it was a good time to reassess the way things are built in her region. She shares that while many sustainability solutions have been developed in response to climates getting hotter and dryer, along the Gulf of Mexico, the challenges are a hot, humid climate that is regularly subjected to hurricane-force winds. And termites.

“We use advanced framing techniques to create strong wood-framed buildings, that are well insulated,” says Bryant. “This means that we right-size and insulate headers, stacking studs where possible, and wrapping the home in continuous insulation to reduce the potential for condensation, which decreases efficiency and can lead to rot.”

Another easily implemented technique that could future-proof homes is to de-couple the systems from the structure. In traditional wood-framed construction, the stud wall goes up, and then holes are drilled through it so electrical wiring can be woven through. Open web trusses and the use of conduits allow system wires to be strung and later replaced, if needed, without taking down walls. By running conduit from electrical panels to the roof, and providing space for future inverters and battery systems, Watershed makes every structure future solar-ready for less than the cost of a nice dinner out.

“Everything we do is designed and built to FORTIFIED Standards,” continues Bryant of the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety’s (IBHS) building certification program designed specifically for resiliency, rather than sustainability. Categorized among three asset types – Home, Multifamily, and Commercial – the FORTIFIED construction method is a voluntary construction standard that goes beyond code to protect against severe weather.”

“In Alabama, insurance companies are required to provide a discount on FORTIFIED structures. This can reduce wind insurance by up to 40 percent,” says Bryant. “That has the attention of homeowners here, and FORTIFIED is becoming the standard. So, while Alabama may be a little behind on sustainability, perhaps we lead the way in resiliency.”

Like her contemporary to the east, Chandra Franklin Womack, P.E., owner and principal engineer for Aran + Franklin Engineering, Inc., in Texas City, TX sees a lot of science-based value in the FORTIFIED Standards.

“As structural engineers, our role is to add strength and longevity to the structure. Aran + Franklin operates from three offices along the Gulf Coast of Texas and one in Florida, so we design custom homes and commercial buildings to withstand extremely high winds and possible flooding,” says Franklin Womack. “In Texas, the homes are generally wood framed, while in Florida concrete is often the primary material. Aran + Franklin is accustomed to working with both.”

As a structural engineer specializing in windstorm design of custom residential, Franklin Womack distills the primary concerns homes face along the Gulf Coast down to wind and water.

“In custom home design, people tend to want a lot of windows on short walls. We build in resisting elements in the form of posts and beams that transfer the load,” says Franklin Womack. In addition to designing homes, she has a significant amount of post-disaster damage assessment experience and knows well the situational defects that cause homes to come apart in extreme weather.

“Water is worse than wind, because of its ability to infiltrate and deteriorate the building envelope,” she says. “However, the roof is where we see the most failure. Once the roof comes off, the water gets in and ruins everything. A FORTIFIED roof incorporates a few enhanced building techniques that reduce vulnerabilities and strengthen the structure in important ways.”

A FORTIFIED Roof designation assures that the roof can better withstand high wind, hurricanes, hail, thunderstorms, and even tornadoes up to EF-2. Features of a FORTIFIED Roof include wind-rated roof covers, wind and rain-resistant vents, sealed roof decks, enhanced roof deck attachments, and impact-resistant roof covers in hail-prone areas. A stronger roof begins with stronger edges. To protect this vulnerable area, FORTIFIED requires specific materials and installation methods, including a wider drip edge and a fully adhered starter strip. Sealing the roof deck beneath the roof covering – shingles, metal panels, or tiles – prevents water infiltration into the home if high winds remove portions of coverings. FORTIFIED also requires ring-shank nails, installed in an enhanced pattern, to keep the roof deck attached in high winds. This simple technique, which requires zero additional effort, nearly doubles the roof’s ability to resist wind.

FORTIFIED Silver meets the roof requirements and adds layers of additional protection. Gable ends, chimneys and attached structures are susceptible to heavy damage in severe conditions. Increased bracing and anchors around these elements prevent them from detaching in high winds. Likewise, FORTIFIED Silver Standards call for stronger garage doors. Finally, FORTIFIED Gold requires an engineered continuous load path, which specifies how the roof is fixed to the walls and how the walls are anchored to the foundation.

Beyond elevating building standards, Franklin Womack sees the FORTIFIED system as a means of increasing certainty and collaboration in the design conversation for custom residential.

“One of the challenges in custom residential is sometimes there isn’t enough collaboration between architects and engineers,” she shares. “In hurricane-prone areas, the structure, the roofing system, and the ability for windows and doors to resist high-velocity impacts are what is going to hold the house together. Better collaboration will allow enhanced building techniques to be integrated seamlessly.”

Franklin Womack suggests that FORTIFIED’s easy-to-use standards checklists offer a simple how-to guide for design professionals wishing to integrate resiliency into their work. She also points out that contractors can also become FORTIFIED Certified.

“It’s very important that structures not only be designed FORTIFIED, but also built FORTIFIED, and that’s where a well-trained workforce comes into play,” says Franklin Womack. To become Certified, industry professionals from across the full spectrum of disciplines – designers, builders, insurers, and others – can benefit from the training offered by the IBHS through FORTIFIED Wise University. Participants must complete a training course and pass the Certification test with a score of 80 or better and prove that they meet the minimum qualifications for certification.

Both Franklin Womack and Bryant agree that where they live and practice, resiliency is the backbone of good design.

“A FORTIFIED home has been designed, built, and inspected by an independent third party, so it is certain to be more resilient than a non-certified home,” says Bryant in closing. “This adds tremendous value to the home in terms of insurance savings, resale value, and when those massive storms come rolling in, peace of mind.”

Bio:

Sean O’Keefe is an who crafts stories and content based on 20 years of experience and a keen interest in the people who make projects happen. You can reach him at sean@sokpr.com | 303.668.0717

from views and vegetation to spatial hierarchy and statistical fractals, biophilia is the spine of good design

Architecture is an experience. Among the best of it, context, character, and community inform place, purpose, and point of view to shape a myriad of choices made along the way. In architecture for learning, the decisions made during design influence a learner’s capacity to absorb and retain information as much as the building provides a place from which a learner obtains an education. For researchers Bill Browning and Terri Peters, Ph.D., infusing the innate human instinct to connect with the natural world into the spaces where we live, work, learn, and play is more than a matter of aesthetics; it is a mission.

“Biophilia is about accommodating the human desire and need to connect with nature in the spaces we occupy,” says Browning, who is the managing partner of Terrapin Bright Green, a sustainability design and research consultancy committed to creating a healthier world. “On the simplest level, biophilic design begins with good views of nature through windows and enlivening the spaces we occupy with plants and natural materials. However, these are just 3 of 15 different patterns of biophilic design that can enhance the built environment. There is no shortage of evidence that these things improve cognitive functions, physical health, and psychological well-being.”

Terri Peters, Ph.D., is an architect and an assistant professor in the Department of Architecture and Science at Ryerson University in Toronto, Canada, who has devoted her career to studying human conditions that are hard to measure.

“The most effective biophilic design solutions are holistic and immersive,” says Peters. “Spatial proportions, the quality of light, textures, air flows, and smells all combine to enhance space in meaningful ways.”

Through nearly 30 years of research and consulting on biophilic design strategies, Browning shares that the established science around infusing space with nature falls into three application areas.

Nature in the Space is the literal idea of adding natural influences like views, vegetation, and daylight to invigorate space by design. The second application, Natural Analogs, is the indirect experiences of nature by including natural materials, fractal patterns, and biomorphic forms in architecture that provide accessibility to nature through non-living elements. Finally, Nature of the Spaces entails spatial experiences that apply naturally occurring spatial patterns that induce a psychological sense of calm and security within a space. For example, unimpeded views through an area enhance prospect awareness, while a wall at your back and a shelter overhead provide a comforting sense of refuge within a space.

“The effects of biophilic design decisions are quantifiable. Studies in educational environments reveal that students learn better, retain more, and enjoy the overall experience of education in spaces with biophilic influences,” says Browning. “Several studies prove that daylight variability improves visual acuity and keep us in tune with our circadian clock. Being able to see nature, even through a window, has an impact on our prefrontal cortex that helps restore our attention and allows learners to increase cognitive focus and information retention.”

According to Attention Restoration Theory, the human brain’s capacity to focus on a specific stimulus is limited – too much time on task results in directed attention fatigue. Breaking away from intense concentration in a restorative natural environment for as little as 40 seconds can reset a person’s mental state from negative to positive, enabling them to resume concentration at total capacity in a relatively short period.

“In educational settings when children are allowed access to nature during the day, teachers report students return to the classroom in a calmer state of mind and are better able to get into the next task quickly,” says Browning.

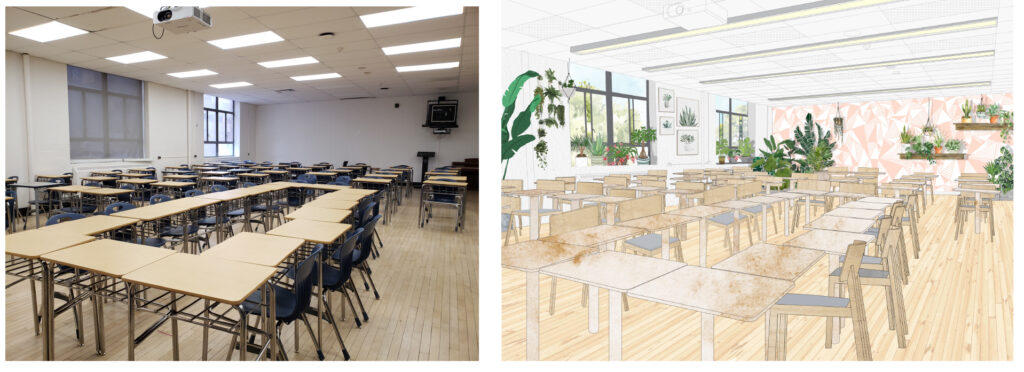

Peters shares that at Ryerson University, while participating in a classroom audit of campus facilities, the team found a lot of challenges related to classroom design, use, and spatial hierarchy.

“Issues as simple as walls cluttered with posters, mismatched chairs, and tables, and poor levels of light are examples of everyday basics that are easily improved,” says Peters. “Next semester, we will establish a test classroom that incorporates biophilic design principles and then evaluate the student and faculty experience against unchanged classrooms in the same building. In addition, we will add plants, replace lighting with a full spectrum system and clean the windows for better light and views. We will also increase spatial variability by adding hierarchy to spaces and replace wall clutter with thoughtfully selected abstract graphics of natural patterns that we believe will have measurable positive impacts.”

One of the most interesting ways biophilic design strategies enhance the experience of space is by incorporating statistical fractals. These detailed, repeating patterns are the fundamental foundation of many organic systems, existing in abundance throughout the natural world. Spiral fractals allow nature to condense itself for strength and durability against the elements; examples include pinecones, pineapples, and hurricanes. A Voronoi fractal illuminates nature’s tendency to favor efficiency and relies on linking cell structure through the shortest path between points. Examples include the skin of a giraffe, honeycombs, the cells in a leaf, and foaming bubbles.

Browning was part of a team that conducted a year-long study using simple biophilic interventions in a sixth-grade mathematics classroom in Baltimore. The changes included removing most of the visual clutter of posters from the walls, putting down carpet tiles with a wavy grass biomorphic pattern, a wallpaper frieze with an abstracted palm-leaf pattern, and automated fabric window blinds with a statistical fractal pattern based on tree branch shadows. Test scores improved dramatically, and through biometric testing, the study determined that the space helped the students with stress recovery.

“Dappled light or the experience of daylight streaming through a canopy of trees in a forest has a calming effect on human minds,” shares Browning. “We recently worked on a new guest room prototype for a hospitality client where we added LED lighting and a perforated metal panel to the ceiling plane above the entrance to the room. When the guest turns on the light, it casts a pattern of dappled light on the walls and floors that mimic the experience of stepping into a forest, which produced a calming effect.”

Browning and Peters agree that the benefits are more than improved cognitive performance when asked about the big-picture necessity for biophilic spaces in learning environments.

“In educational design, there is an ever-increasing pressure on physical spaces to offer more than mere shelter. To be competitive, Spaces need to enhance collaboration, elevate our mood, and make people feel calm and welcome,” says Peters. Unsurprisingly, Browning reveals that the corporate world leads the way on biophilic implementation in many cases.

“Corporations now realize the old model of cubical-fill workspaces don’t favor chance interactions and the sense of spontaneous combustion that compels the eureka moments that can change the trajectory of success,” says Browning. “To maximize the value of the real estate, workspaces and classrooms alike require openness, inclusivity, and the opportunity for cross-pollination among interactions.”

Browning points out that for much of his 30 plus years of experience in the field, energy efficiency has been the focus of sustainable design strategies. In the push for planet-saving sustainability, many have overlooked the fact that the cost of operating a building is only about one percent of a business’s expenses. The real value in sustainability is gained through increased human performance, personal pride of place, and the sense of satiation that comes from having access to fresh air, views of nature, and engaging interactions with others.

“In some ways, the effectiveness and simplicity of these design strategies can be intuitively obvious,” finishes Peters. “Biophilic design aims to be an immersive, multi-sensory experience of nature in space. However, there’s more to it than plants and views or bells and whistles. It’s about using color, light, texture, and nature’s ability to improve human performance. These principles can be transmitted to everything from carpet patterns to the angle of a desk to a window. In every way possible, design makes a difference.”

Bio:

Sean O’Keefe is an who crafts stories and content based on 20 years of experience and a keen interest in the people who make projects happen. You can reach him at sean@sokpr.com | 303.668.0717 .

thought leadership from the front lines of smart building technology, implementation, and long-term performance

Smart technologies of every sort continue to seep deeper into our lives, putting information, services, comfort, and convenience at our fingertips where ever we are. In today’s smart buildings seemingly, anything and everything can be automated. From individualized thermal comfort to supplemental lighting that responds to ambient daylight and increasingly untethered global connectivity the limits of technology are all being integrated to the point of becoming conventional. In a Round Table conversation, Colorado Construction & Design was delighted to discuss the amazing present and super bright future of Smart Buildings with a group of dedicated professionals committed to smartly engineering, efficiently building, and acutely commissioning technology-infused facilities in Colorado and across the country.

Our Panel

Renée Azerbegi, Ambient Energy

President and founder of Ambient Energy, Renée Azerbegi loves making a positive impact in the commercial building industry and on the environment through personal determination and her firm’s collective depth of experience. Ambient Energy offers a suite of services focused on building and system analysis to optimize new construction projects for operational efficiency and longevity; evaluate and improve the performance of existing buildings; or commission either as a third-party engineer. Utilizing fault-detection diagnostics and monitoring-based commissioning, Ambient Energy strives to ensure buildings operate as efficiently as possible through the whole of their lifecycle.

Bret Roberts, P.E., Control Solutions Inc.

Co-founder of Control Solutions Inc. Bret Roberts relishes the thrill of making things work, planning and seeing a complex building together from start to finish is both his business and his gratifying reward. Along with partner, Ed Welch, Roberts established Control Solutions, Inc. in 2007 by merging a wealth of experience in building automation service and installation. Gary Bales became a partner in the practice in 2013. Control Solutions Inc. contends for smart system installation projects from Colorado Springs to Fort Collins and works with clients to update and retrofit existing buildings with more advanced systems as buildings age. The firm represents Honeywell Building Automation products such as Tridium/Niagara, Honeywell WEB’s, Spyder Controllers including the new CIPer product family of controllers and I/O Modules.

Ryan Sobeck, Siemens

A Territory Sales Manager at Siemens, Ryan Sobeck began his career in electronics working on M1 Tanks and Bradley Fighting Vehicles in the Army before getting into building automation systems implementation, design, and products 24 years ago. Today as a representative of Siemen’s Building Technologies, Control Products and Solutions, Ryan’s territory spans from Colorado north through Wyoming, Utah, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, and up to Alaska. Siemen’s showcases technology that integrates HVAC, lighting, shades, and plug loads from a single, ethernet-connected, terminal controller. Within the Building Technologies division of this global giant, Siemens is using integrated smart building technologies to optimize space and improve people’s lives.

Our Conversation

While integrating systems and technology to enhance the user experience is fundamental to smart building design, bells and whistles alone aren’t enough to make a building smart. What does?

“It starts in design,” says Roberts. “If the design is well thought-out, the rest of the project will follow that path, but if you start with a poor design it’s almost certain the finished building will underperform.” Roberts and his firm Control Solutions Inc. are among those responsible for installing the systems that have been selected and as such often feel the brunt of any bad decision making related to systems chosen in design. The technology of controlled systems has changed significantly, and everyone involved needs to be thinking holistically about smart systems, smart design, and smart installation.

“Having an owner who is driven, experienced, and knows what they want in terms of building performance almost always sets the stage for success,” adds Azerbegi, whose firm, Ambient Energy, can find itself in both pre- and post- construction roles depending on the project. “Smart design isn’t just technology, it’s holistic strategies like envelope modeling and commissioning to determine if the building is well-sealed. If it’s not, the best systems in the world won’t make it a smart building for long.”

Azerbergi points out the need for better documentation on the intended sequence of operations from mechanical and electrical engineers in the design stage to eliminate the possible risks of misinterpretation during installation. Ambient Energy likes to incorporate a series of controls integration meetings both in design and during construction to ensure efficient systems are being implemented and everyone involved is speaking the same language. Roberts is excited to share that common language has arrived.

“ASHRAE’s newest guideline, issued in July 2018 establishes a set of standardized advance sequences of operation for common HVAC systems,” says Roberts with a copy of the new standards proudly at the ready. The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers or ASHRAE, has been devoted to the advancement of indoor-environment-control technology since it was formed in 1959. ASHRAE Guideline 36-2018 provides uniform sequences of operation for HVAC systems that are intended to maximize energy efficiency and performance, provide control stability, and allow for real-time fault detection and diagnostics. “I’ve been wanting something like this for a long time,” continues Roberts. “We need more of a common language around buildings systems and this guideline establishes a starting point that will still allow for individual and situational customization.”

The advantages of high-tech digital connectivity, functionality, and comfort have been realized in office environments and homes for some time. Where are we going next?

“Individualized controls and data harvesting are starting to be integrated into smart-phone platforms,” says Sobeck of Seimens, a technological pioneer of electrification, automation, and digitization systems and products. One such system called Comfy Comfy allows users to request heating or cooling changes, via a smartphone app, directly to the building automation system. This data can then be used to tell individuals which spaces in the office best suit their needs at any given time, ideal for free-address offices on the design desks today.

The ability to gather an immense volume of data on a smart building is what allows it to be customized around the user experience. However, analyzing and appropriately reacting to that same abundance of information is central to ensuring a smart building operates effectively day-to-day. The ability to detect, identify, and individually correct faults within a smart building system is an advantage that is easily mitigated if the building’s operation team isn’t actively monitoring and fine-tuning the system. Operators have to wield the building’s technology to save effort, expense, and all three of the Round Table participants agree there is definitely a cost of doing nothing.

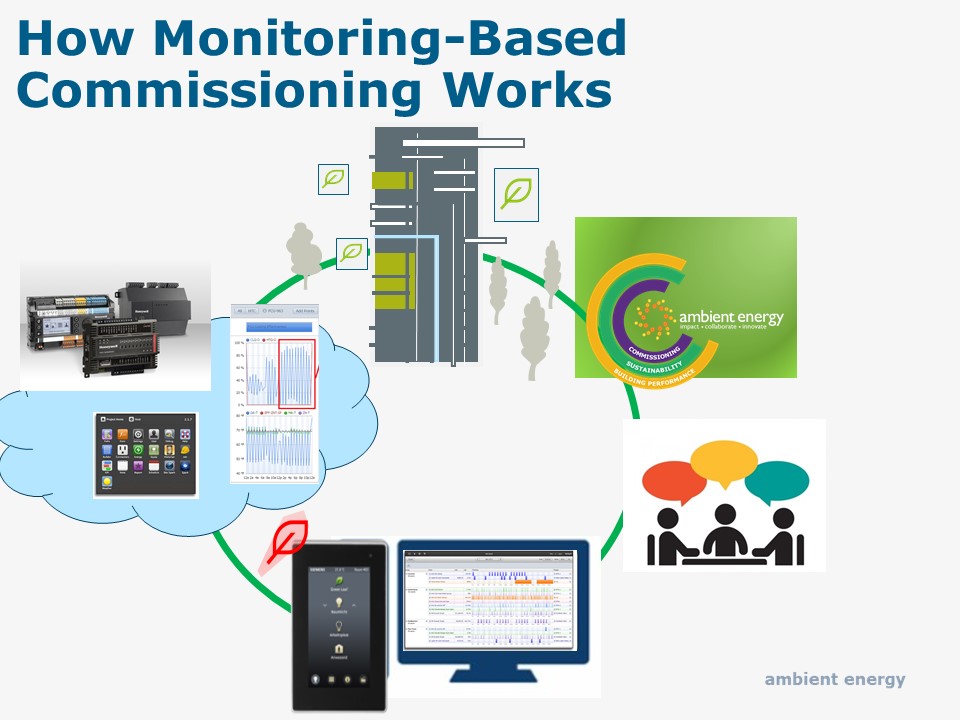

“Buildings will drift upwards in energy consumption by some 2- to 3- percent a year if they aren’t actively managed,” says Azerbergi, whose role in commissioning buildings has her firm on the front lines of evaluating long-term operational expectations as the building comes to life. Though commissioning is generally required by code, most owners would probably be surprised to know that typical commissioning processes actually only test a sampling of unitary equipment rather than 100%. Perhaps more importantly, commissioning of a new building does little to account for the building’s performance once commissioning is complete unless the building operator actively monitors and controls it. “Monitoring-based commissioning integrated with fault-detection diagnostics is what we recommend,” continues Azerbergi about the need stay on top of what is happening as users occupy and make spaces their own. “Continual monitoring has been shown to save 5 to 15 percent on annual energy costs, eliminating energy drift, improving performance, and increasing user comfort.”

What does the integration of all these technologies mean for designers and builders?

The answer, it seems, is the need for yet more and better integration among the industry’s diverse range of professionals to match the requirements of changing technologies.

“For the last forty years or so, controls were the responsibility of the mechanical and lighting was the responsibility of electrical engineers,” says Roberts of a dichotomy that feels needlessly siloed, occasionally detrimentally. In today’s smart buildings’ just as systems need to talk to each other and be monitored holistically and individually, the design, implementation, commissioning, and operations processes also need to be more seamlessly integrated.

“Investing an afternoon in making sure the sequence of operations meets the owner’s objectives and the designer’s intent is essential with the systems going into today’s smart properties,” says Sobeck. Azerbergi agrees, adding that a commitment to collaboration on the technology choices and expectations will greatly reduce issues found during the commissioning process. Pre-thinking challenges together focuses the whole team on developing the best possible building for the owner’s investment.

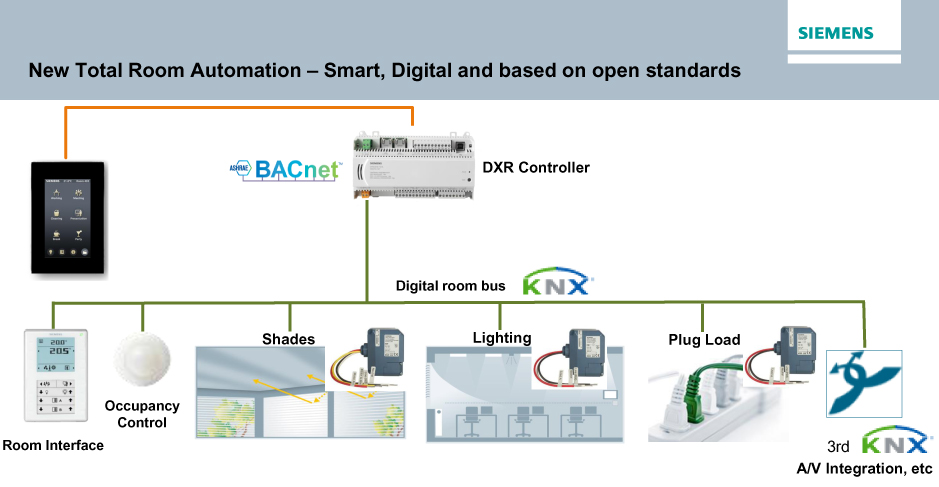

As user expectations of workspaces have grown beyond simply hot or cold and on or off, product manufacturers have continued to push toward integrated solutions. Siemen’s DXR Controller is a single-source, remote-monitored control unit for the building’s temperature, lighting, window shades and electrical loads. On the building side, more complicated systems don’t necessarily mean more complicated construction, as long as advance coordination and an appetite for new knowledge are fundamental to the builder’s goals.

“Owners have been installing two, three, and sometimes four different control systems in a single building,” continues Sobeck, adding depth to the need for better integration in all aspects of the industry. “Single-system solutions mean one product, one installation subcontractor, and a more integrated, informed understanding of systems for optimal performance.”

Control Solutions Inc. competes for systems installation opportunities and also represents Honeywell building automation products including the CIPer product family of controllers and I/O modules. As a subcontractor helping designers understand smart systems, install, program, and start them up, Roberts sees a commitment to continuing education as essential for his firm and staff

“You can’t have too much education on all of this,” says Roberts of the continued trend toward more integrated systems requiring highly specialized and multi-faceted experts. “The systems are getting so complicated that finding enough skilled people capable of putting these systems together is my biggest challenge.”

Control Solutions Inc. is proud to represent Honeywell Building Automation products including Niagara 4 software and the new CIPer product family of controllers and I/O Modules.

Roberts nudges the green ASHRAE Guideline 36-2018 on the table forward as a next step that can be taken, immediately, industry-wide to facilitate better communication and collaboration. The complexity of systems and what is required of the professionals who design, sell, program, install, commission, or operate them will continue to increase as smart buildings and smart people get smarter out on the edge of technology and convenience.

About the Author

Sean O’Keefe is an who crafts stories and content based on 20 years of experience and a keen interest in the people who make projects happen. You can reach him at sean@sokpr.com | 303.668.0717

Architectural writer, Sean O’Keefe gathers keen insights on the intersection of place and possibility from a few in the know

Placemaking – A Round Table Conversation

Placemaking – A Round Table Conversation

Originally published in Colorado Construction & Design

Spring 2019

By Sean O’Keefe

Architecture begins with three fundamentals, defined by Roman architect, engineer, and builder Vitruvius as “Commodity, Firmness, and Delight” or said another way – Purpose, Structure, and Pleasure. Placemaking strives to take those ambitions a step further by celebrating the public spaces that connect us to our homes, our work, our fun, and to one another. From imagining the possibilities to helping others realize them on the grandest scale, placemaking is about people. Colorado Construction and Design was pleased to convene a roundtable discussion to learn more about the triumphs, challenges, and state of placemaking in Colorado through an esteemed panel of professionals.

Placemaking Panel

Charlie Nicola – Brookfield Properties

A Senior Vice President with Brookfield Properties, for the last 18 years Charlie Nicola has been a leading figure in the redevelopment of the former Stapleton International Airport into a thriving community of 12 neighborhoods. Prior to that he had a hand in the development of Coors Field and takes pride in the possibility of place as a social stimulant. Despite the risk and responsibility of development, Charlie truly enjoys the collaboration and comradery of the creative processes that are the foundation of placemaking. The greatest rewards of his work are in seeing spaces becomes places when they are ignited by people and purpose.

Laurel Raines – Dig Studio

A founding partner at Dig Studio, landscape architect Laurel Raines has positively shaped the exterior public realm of neighborhoods throughout Denver and Rocky Mountain communities for over thirty years. After working as a Design Principal with the international landscape architecture firms of EDAW and AECOM, Laurel formed her own firm, Dig Studio, in 2012. She has spearheaded project initiatives which have changed community perceptions of the role parks, plazas and streetscapes play in evolving a Western landscape aesthetic. Today Dig Studio is leading transformational redevelopment projects that are positively reshaping Denver’s urban fabric.

Mitch Black – Norris Design

Mitch Black will tell you that storytelling is central to placemaking. He’s been on the front lines of placemaking for the last 25 years as a planner and landscape architect at Norris Design, where he is a principal. He enjoys helping to lead a firm with a strong and diverse portfolio and seeing the cross-pollination of ideas that come from many different approaches to landscape design, planning, and real estate branding. From corporate settings to highly-animated community gathering, T.O.D., sports and streetscape projects, where the built environment meets the natural one, Black and the Norris Design team help clients plan a vision and bring it to life.

John Buteyn – Colorado Hardscapes

John Buteyn was 18 when he became the first person the owner of Colorado Hardscapes hired after his own two sons. Forty-seven years and a few job descriptions later, John and everyone at Colorado Hardscapes still apply curiosity and commitment to building the hardscape features that are the infrastructure of place. Building on three generations of both utilitarian flatwork and decorative concrete, Colorado Hardscapes’ expertise also includes water features, sculpted concrete and rockwork, and interior concrete. Noteworthy landmarks include Denver Union Station, the Streets at Southglenn, and the massive, new Gaylord Rockies Hotel and Convention Center.

What makes a design more than design, what makes it a place.

What makes a design more than design, what makes it a place.

“Every place starts with the site,” says Mitch Black. Design influences start with the site’s attributes, context, audience, and purpose. The positives and negatives of the physical environment surrounding the project all have an important role in shaping the initial concept. Amazing view planes must be preserved and framed by the site. Accounting for rough edges in gritty urban or industrial settings can be done through buffering or embracing those attributes, but decisions must be holistic, with long-term objectives in mind. “Placemaking is about storytelling, every site that becomes a place must tell a story and the story must have meaning to the people who use the site.”

Charlie Nicola agrees, suggesting that the public’s embrace of place happens when design fosters human interaction and the place becomes a conduit for social connectivity.

“There has to be some there, there,” says Nicola succinctly. In order for a place to attract sustained social attention and become a routinely popular destination, it needs to have some meaningful gravity of its own. From the development perspective, placemaking is often about finding the path of least resistance to the critical mass. Nicola’s work on Coors Field centered on capturing a postcard corner at 20th and Blake Street in front of the ball park. Working with Laurel Raines, placemaking gestures begin building anticipation for the excitement of gameday several blocks away. A combination of street lighting, landscape features, and artistic elements help bring the massive building down to human scale. “Effective placemaking happens when the site’s positives spread beyond the original boundaries, allowing that sense of place to grow positively beyond the site as it has in the case of the Ballpark neighborhood.”

Making a positive contribution that extends further than aesthetics is fundamental to Laurel Raines’ work at Dig Studio.

“Communication, collaboration, commitment, community, and care,” she shares. “These are the fundamentals of effective design, in placemaking they must converge to produce a space that makes life better for all.”

There are many competing and, occasionally, contradictory factors that drive decision making in commercial development. How do you keep the importance of place alive in that conversation?

“From an investment point of view, we have to understand the importance of place as part of the commitment we make to the communities we are working in,” says Nicola. “If it matters, then it matters.”

Effective development is about getting more for your investment, not less. Nicola relies on the thoughtful expertise of firms like Norris Design, Dig Studio, and Colorado Hardscapes to give him the raw, honest realities of what he is asking for and what it costs.

“Certain things, like sidewalks, have to be built, and there are any number of design treatments that can be applied to a sidewalk to bring it to life,” says Black. “We model design solutions and costs concurrently and identify key features of the landscape design and site ornamentation that establish it as a place.”

Echoing Raines’ sentiments on collaboration, communication, and commitment, all agree designing something that can be built and maintained is the result of distilling lots of good ideas from lots of determined professionals into a cohesive whole. Advance coordination with a decorative concrete contractor or other acutely specialized contractors in the design phase is the surest way to eliminate cost-cutting measures that can diminish the presence of important components somewhere between concept and completion.

“I really love watching children run through the water features we created at Denver Union Station and Stapleton,” says John Buteyn. “In everyday use, you can see which elements engage people and make them want to stay.” Elements that make people want to linger are essential, but owners and designers must also have an appreciation for the fact that water jets and fountain features have long-term costs. Annual maintenance on a complicated water feature can be as much as five percent of the construction costs, a financial reality that must be understood from inception. If not, the risk is a white elephant, an undesirable possession that is simply too expensive to maintain in proportion to use but difficult to discard profitably.

What is the state of placemaking in Colorado today?

“In multi-family housing developments plenty of non-public green space is being accounted for,” says Raines. “The more interesting opportunities to me are in urban settings where the integration of parks and green space has not kept pace with the influx of new residents – a challenge Denver Parks and the Downtown Denver Partnership are actively addressing.” Indeed, a 2016 study by University of Denver graduate student Ryan Keeney while working with Denver Infill found that a total of 237 acres were exclusively committed to surface lot parking in downtown Denver alone.

The Heron Pond / Carpio-Sanguinette Park Master Plan + Design commissioned by the City and County of Denver aims to revitalize a series of isolated parcels along the South Platte River as the largest natural area in the Denver park system.

Dig Studio is currently in the midst of an urban reclamation project for the City and County of Denver. The Heron Pond / Carpio-Sanguinette Park Master Plan + Design aims to unify multiple City-owned properties trapped along a forgotten stretch of the South Platte that have fallen victim to neglect and environmental misuse. The plan envisions more than 80 acres along this blunt edge of industrialization as the largest natural area in the Denver Park System.

“In many urban projects, we are seeing smaller landscaped spaces that are more densely amenitized,” says Black. The trend is indeed evident in many of the office, mixed-use, and multi-unit living projects taking over Denver’s surface lots as they are redeveloped, each bedecked in a collection of outdoor lounges, pool decks, plaza entryways, and terrace overlooks. Bringing the outside in, planters, irrigation, drainage, year-round vegetation, and Colorado sunshine are also prevalent in today’s well-developed commercial properties.

In Colorado’s smaller communities, the Round Table participants generally applauded municipal clients for getting ahead of future congestion by effectively incorporating green spacing in governmental development and encouraging it in the commercial sector. Norris Design is working on Miller’s Landing, a mixed-use development intended to connect the town’s newly developed Phillip S. Miller Park with Castle Rock’s downtown core. The project seeks to remediate nearly 100 acres of former landfill with a mix of uses like office, hotel, entertainment, and retail joined by a series of interconnected public spaces. Big or small, urban or remote, placemaking requires a team of professionals able to work effectively with the community to understand the local concerns, needs, and wants that should beneficially influence the place they create.

“Building community buy-in is an important part of placemaking especially when change is on the table,” says Raines. Community outreach processes implemented by designers and developers often help residents understand how vibrant public spaces can improve human connections and quality of life.

Miller’s Landing in Castle Rock is a positive example of sustainable suburban forethought and encouraging greenspace development in stride with commercial investments.

What are the challenges of placemaking?

“The honest answer is entitlements,” says Nicola, a statement that is greeted by a palatable sense of agreement around the table. Beyond his leadership in the creation of Coors Field and Stapleton, Nicola was the Construction Director and Owner’s Representative for the Denver Bronco’s $400 million stadium and he’s spent decades on projects with the highest levels of complexity the field has to offer.

“Placemaking is about establishing a vision and achieving it. The beneficiaries of better places are communities,” continues Nicola. “I solve the problem of red-tape by hiring the best consultants I can find and asking for a lot.”

Black and Raines nod knowingly and the group discusses recurring entitlement and approval process problems that design and construction projects of every magnitude and purpose seem to face. Many in the industry are fatigued by continually having to routinely build new relationships with individual personalities at several entities with potentially subjective and, occasionally, contradictory interpretations of building codes and regulations on every project they undertake. Many suburban municipalities also seem to share a certain sense of stubbornness on collaboration. A municipality’s unwillingness to move much further than their own initial understanding can lead to a repetitive, formulaic expression of place. Even routine requirements like a road closure can feel contentious on the consultant’s side of the counter, where it’s best to simply try to follow the rules and be proactive with permitting when possible.

“Once you get the place designed, the work isn’t over,” says Black of the process of turning his drawings over to a contractor for execution and then shepherding it for many months while the work is realized. Projects remain under pressure throughout construction – affordability issues, schedule, entitlements, approvals, logistics – each of which can degrade a design, if not properly managed. “One of the biggest challenges is making sure the design lasts throughout the process; that the story and design intent are clear in the finished product.”

Buteyn agrees and as the contractor at the table, understands the importance of achieving the owner and designer’s vision down to the smallest detail wherever possible. When the intent is achieved in placemaking it’s usually fairly easy to see if the original vision for a place is successful.

Colorado Hardscapes was involved in the redevelopment of Denver Union Station, and there is likely no better example of effective placemaking in all of Colorado. Where only just a few years ago there was a large neglected property whose only purpose was to serve the nearly-nonexistent Travel by Train crowd, today Denver Union Station is a place filled with people, food, spirits, smiles, profit, possibility, purpose, and play inside and out. An entire new epicenter of the City has emerged in the new heart of Denver, and on a warm summer’s day with nothing to do it’s definitely a special place to be.

“It’s a wonderful feeling to be involved in helping make these places come to life,” finishes Butyen. “Special places are worth the work and worth the investment because special places are where memories are made.”

About the Author:

Sean O’Keefe is an who crafts stories and content based on 20 years of experience and a keen interest in the people who make projects happen. You can reach him at sean@sokpr.com | 303.668.0717